Fewer than 1,000 people live in Valders, but this rural slice of Manitowoc County is dealing with toxic chemicals that have vexed far bigger municipalities and created health risks for scores of Wisconsinites.

And it's hard to tell these days when the village will ever get help cleaning up the contaminants.

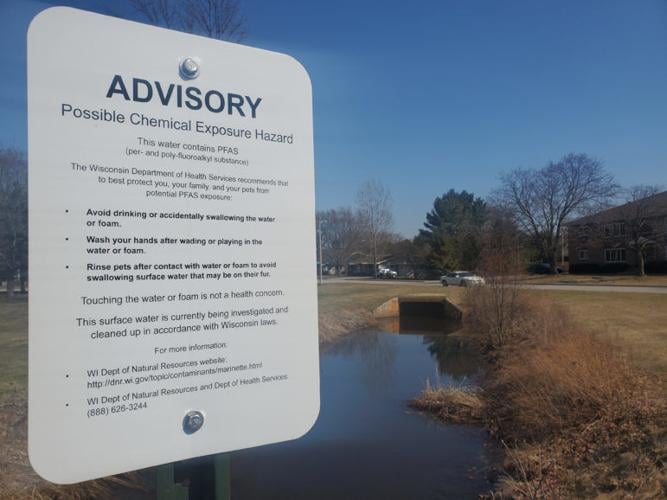

The chemicals, called PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, have been omnipresent in everything from firefighting foam to non-stick pans and studies have linked them to cancer, small birth weights and other health problems. They're called "forever chemicals" because they can take centuries to break down in the environment, if they ever do.

The Environmental Protection Agency made waves last week when it announced that, for the first time ever, the federal government will set strict standards on those chemicals in drinking water.

The goal is to have zero of the most common types of PFAS in drinking water, but there is a hard cap limiting the chemicals to 4 parts per trillion. That's equivalent to four drops in half a million barrels of water.

Environmental groups and state lawmakers hailed the new federal standards as a huge development.

But local governments, utilities and others will have about five years to get their PFAS levels to meet standards, while hundreds of thousands of Wisconsin residents potentially drink water with chemicals above those levels.

In Valders, the level for one of the most common types, PFOS, was below targets set by the state but not low enough to meet the new EPA standards.

“It is gonna be a challenge,” said Austin Shillcox, Valders’ director of public works. “We don’t know what we are going to do yet.”

Federal money will be available to help upgrade water systems to comply, though it is uncertain when the $1 billion available might start rolling out.

In Wisconsin, Republican legislators and Gov. Tony Evers are deadlocked over the framework to spend $125 million allocated in last year’s budget to help with PFAS cleanup.

Last week, Evers vetoed legislation to lay out a blueprint for spending the money, arguing that the bill shields polluters from accountability — a claim Republicans have rejected.

“We will continue to work with the governor, the DNR, the Legislature, whoever it takes to find that common ground,” said Jerry Deschane, executive director of the League of Wisconsin Municipalities. “Because you know, the EPA basically started a clock ticking — we've got to get something done.”

EPA rules could affect 355,000 Wisconsinites

The EPA says its new rule will reduce PFAS exposure for 100 million Americans and that as many as 10% of the nation’s public drinking water systems will need to take action to comply.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources’ standard for certain PFAS in drinking water is 70 parts per trillion, which will remain in effect until the state drafts new rules that comply with the federal standards.

Starkweather Creek, pictured in May, flows through Dane County Regional Airport and Truax Field in Madison and contains high levels of dangerous "forever chemicals" known as PFAS.

The DNR has pointed to testing data that show the overwhelming majority of Wisconsin drinking water systems already comply with the new federal levels. However, the environmental advocacy group Clean Wisconsin estimated that 355,000 residents get their drinking water from systems that would not meet the new EPA standards.

In Madison, where PFAS have been uncovered in Starkweather Creek and Lake Monona, the city says its drinking water would comply with any potential federal standards.

In Valders, drilling a new well is a distinct possibility, Shillcox said. The contaminated well has been shut off, but a long-term solution is needed to help provide enough water for the village's residents.

This would be a time- and money-intensive process that requires searching for a suitable location, buying the land and conducting studies to make sure the village can pump up to 120,000 gallons of water per day that it needs.

Debate over state funding continues

Communities across the state have been split on their support or opposition to the bill approved by the GOP-controlled Wisconsin Legislature, which would have created grant programs to help municipalities conduct PFAS testing or invest in drinking water systems, as well as assist landowners affected by contamination.

Lee Donahue, a board supervisor in the La Crosse County town of Campbell, argues it's a “bad bill” that could “cause residents to compete with industrial and corporate entities for money” set aside in the $125 million budget.

In Campbell, which is near the La Crosse airport, where firefighting foam containing PFAS has been used since the 1970s, chemical levels were so high that the state Department of Health Services issued a health advisory in 2020 and many residents have been drinking bottled water ever since.

“Today we are no closer to accessing the $125 million dollar trust fund which has sat idle since the budget was passed,” Donahue said in a statement Tuesday.

Officials in the town of Peshtigo lobbied Evers to sign the bill. Peshtigo's issue with PFAS is traced to nearby Tyco Fire Products, which for decades manufactured firefighter foam that contained the toxic chemicals.

In 2022, the town sued Tyco, its parent company, Johnson Controls, and scores of other companies involved in manufacturing PFAS. Peshtigo's lawsuit argues the chemicals are “a public nuisance” that threaten the health and wellbeing of residents.

Amid all of this, some residents spread biosolids on their fields that inadvertently contained PFAS after receiving a permit from the DNR to do so.

Jennifer Friday, board chair for Peshtigo, said there is a worry that the DNR could hold them accountable for the chemicals’ proliferation in the town.

“What is the problem with giving some people that peace of mind saying no, legally, they cannot do this to you?” Friday said.

The proposal Evers vetoed included a provision that would exempt anyone who participates in a grant program targeted at “innocent landowners” from facing enforcement action by the DNR.

Gov. Tony Evers wants legislators to approve his plan to use $125 million to combat PFAS in Wisconsin.

Evers said the provision could be interpreted to include those who caused the contamination in the first place and that it would limit the authority of the DNR to take action.

“I will not sign legislation that has any chance of letting those who cause PFAS contamination off the hook for remediating their contamination,” the governor wrote in a veto message.

The bill’s authors, Sens. Eric Wimberger, R-Green Bay, and Robert Cowles, R-Green Bay, pointed to a memo from the Legislature’s nonpartisan legal staff saying the bill does not “provide any general exemption from DNR enforcement that would apply to a business that recklessly or intentionally caused PFAS contamination.”

The memo does note that there might be circumstances where a person who “recklessly or may have intentionally caused PFAS contamination” would be included in the innocent landowner program.

“Every person in Wisconsin deserves to have clean, safe drinking water, and the governor denied them that,” Wimberger said in a statement.

What happens now for PFAS funding?

Evers has gravitated toward his own plan for spending the $125 million, a proposal that has sat untouched in the Legislature’s budget writing committee for weeks. The governor's plan, unlike the Legislature's, would have given the DNR more flexibility on how it spends the money without approval from the Joint Finance Committee.

In a bid to force the hand of legislators, the governor called the Joint Finance Committee into a meeting to take up the PFAS funding, as well as $15 million in aid for healthcare providers in western Wisconsin.

Sen. Howard Marklein, R-Spring Green, and Rep. Mark Born, R-Beaver Dam, who co-chair the committee, said Evers’ move was nothing more than “playing politics.”

An angler fishes along the eastern shore of the Peshtigo River in September 2021. The town of Peshtigo sued Tyco and Johnson Controls over PFAS contamination and is struggling to come up with money to deal with the toxic chemicals.

Meanwhile, some communities have already accessed federal money related to PFAS.

But that process is not always smooth. Aid for Peshtigo came with a catch: A federal grant of over $1 million required the town to provide $400,000 in matching funds, money it doesn’t have.

It could be months or longer before the federal money set aside by the Biden administration to address PFAS begins flowing to local governments. It's also unclear how much of the $1 billion will ultimately be set aside for Wisconsin.

If state and federal aid is insufficient, some have worried that utilities would have to increase rates for customers to cover the cost. For those areas where the utility is municipality owned, property taxes could be on the rise.

“You know, it's the same old story,” said Deschane, from the League of Wisconsin Municipalities. “The buck stops at the local level, one way or the other. These local governments, these … water systems are going to have to find the financial resources to address this problem.”

The Peshtigo town chair, Friday, said the back and forth in Madison over PFAS cleanup policies is growing old.

“Until someone can prove to me otherwise, I think this is all politics,” Friday said. “You know, one side can't let the other side have a win, if you will. And it's really too bad.”