For years, Hetti Brown has brainstormed how to address “energy poverty” in Wisconsin’s Driftless region.

Brown is executive director of Couleecap, a community action agency that helps those living in poverty with food assistance, housing, transportation and other needs in southwestern Wisconsin. Some of those residents pay 16% to 30% of their income to heat and power their homes — compared with an average of about 2% statewide, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

“The highest amount of that energy cost across our area is electricity,” Brown said.

Couleecap has long been a leader in helping Wisconsinites weatherize their homes to help reduce energy burden. Brown has been searching for ways to advance that work by bringing solar power — and its savings — to Couleecap’s community.

“How can we build a community solar garden dedicated to low-income communities? That's how it all started and we brainstormed around it,” Brown said.

The result of that brainstorming came in the form of a partnership between Couleecap and a local utility, Vernon Electric Cooperative. With help from a $250,000 grant from the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin, Couleecap buys — or subscribes — to the energy output of 550 panels of a recently built community solar garden on behalf of 137 households with the highest energy burden in Vernon Electric’s territory.

Couleecap will act as a proxy subscriber for those residents for 10 years, enabling access to about 1.5 megawatts’ worth of power, saving an estimated $225 a year on their electric bills, a 10-12% reduction. Last month the first bill credits went out.

“This is the first of a kind in Wisconsin,” Brown said. “This is the first time low-income populations have access — barrier-free, cost-free access — to community solar.”

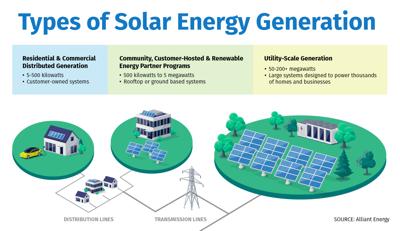

Community solar projects are generally 1 to 5 megawatts in size, spanning 30 acres or less. They are much smaller than utility scale solar power plants but larger than home rooftop arrays.

This relatively novel model of building small scale solar projects and distributing the energy locally is democratizing access to renewable energy across the country, reducing electricity costs for subscribers and rapidly expanding the solar energy portfolio at a time when climate change threatens society’s economic and environmental stability.

What’s holding the Badger state back from advancing in community solar development is policy, specifically the lack of one. Wisconsin has no legislation on the books to allow or incentivize third party community solar. A bill pending in the Wisconsin Legislature would pave the way for community solar, but with the legislative session soon to close, its passage is unlikely.

Brown sees community solar as a way to address energy poverty in Wisconsin.

“These disparities are growing every day as utility costs get higher and higher and higher,” she said. “We cannot afford to leave the low-income population behind as energy efficient technologies become more available.”

Accessing the sun

For your electricity to be solar powered, you generally need three things: a house you own, a quality roof, and about $20,000.

Those ingredients are out of reach for about 50% of the population, said Molly Knoll, vice president of policy for the Coalition for Community Solar Access (CCSA), a trade association for the industry.

Community solar, also called distributed solar, allows a third party — someone other than a utility or homeowner with a rooftop solar array — to produce solar power. In typical community solar projects, subscribers pay a fee to a local solar garden for the output of a certain number of panels. The power generated by the panels flows to the grid and members receive a reduction on their electricity bill.

“The nice thing about community solar is that you get to have a relationship with your solar farm, you get to know that you're getting green energy, and most importantly you get the benefits of the clean energy transition in terms of lower electricity rates,” Knoll said.

Community solar is a policy “Swiss army knife” and a unique opportunity to advance multiple priorities, she said.

“It helps with job creation, it helps with energy equity problems, it helps with renewable energy deployment,” Knoll said.

Climate change shrouds the renewable energy transition with a sense of urgency — the clock is ticking on quitting fossil fuels. Another selling point for community solar is that it’s fast.

“From when legislation passes and a commission gets regulations up and running, you can see solar panels in the ground in nine months or less,” Knoll said.

The role of law

Community solar deployment requires two things — access to the grid and access to the utility bill. In Wisconsin, those access points are controlled by the utilities, who Knoll said aren’t likely to relinquish control if they don’t have to.

“There's really no place in the country where community solar exists without the legislature having instructed the (regulatory) commission and the utilities to start making this offering,” Knoll said. “So we are telling all the states, particularly Wisconsin, whether it's pending legislation, you know, hop on this, get this passed.”

In Wisconsin, only utilities have the power to sell energy. Third party community solar installations will need their utility to accept the energy they produce, distribute it, and credit local subscribers with bill savings. Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia have policies enabling third party community solar.

“Our initial concept was that we use sort of what they have in Minnesota,” Brown said of the Couleecap community solar project. “But unlike Minnesota, we don't have the regulatory environment that would allow that.”

Sen. Duey Stroebel, R-Saukville, is seen at the State of the State address at the Capitol in Madison, Wisconsin on Jan. 24, 2018. Stroebel has proposed community solar legislation he thinks would create competition and lower energy costs in the state. (Coburn Dukehart/Wisconsin Watch)

In 2013, Minnesota passed a bill that enables third parties to build and manage community solar gardens. These small-scale, localized projects have grown in Minnesota more than almost anywhere else in the U.S., with the state hosting over 800 megawatts of community solar capacity, far outpacing what they produce in individual rooftop solar.

“The utilities don't want other folks providing energy in their service territories. They're a monopoly and they like it that way,” said Knoll. “That's where legislation comes in because the utilities will do what the policymakers instruct them to do. But the policymakers need to speak up.”

The lawmaker speaking up in Wisconsin is Sen. Duey Stroebel, a Republican representing District 20 in eastern Wisconsin, encompassing communities around Lake Winnebago, down to the outer Milwaukee suburb of West Bend.

Stroebel introduced legislation to allow for third party community solar in Wisconsin. He told the Cap Times his proposal is “an innovative way to provide choice to consumers” and encourages competitive prices in the electricity field.

“The power industry in the state is monopolistic and we understand why for certain reasons,” Stroebel said. “But we have the ability to create some competition.”

The case for farms and business

On Valentine’s Day, John Schulze sat down in front of the microphone in a Wisconsin state Capitol hearing room and said, “It’s time to legalize it.”

After a pregnant pause he added, “And by ‘it’ I mean community solar.”

Schulze is director of legal and government affairs with Associated Builders and Contractors of Wisconsin, an organization that represents small and medium-size contractors.

Community solar projects would provide work for his members, Schulze said. Solar construction work is presently out of reach for those contractors, he said. Utility scale projects require hundreds of workers to do the job, often sourcing them from out of state. With a more manageable size, community solar construction work could be done by his members, Schulze said.

“You don't have to mobilize and bring in an army of people from a huge firm outside of Wisconsin. You can just do it locally,” Schulze told the Cap Times.

Stroebel’s bill would require a two-thirds vote by the local government to approve community solar projects, a stipulation he says allows for citizen input.

That’s “unlike these large 1,000-plus-acre utility scale solar developments that only have oversight from the Public Service Commission,” Stroebel said.

Large utility scale solar power plants have caused tensions in rural communities, specifically for farmers who worry about the ripple effects of taking thousands of acres out of agricultural production.

Stroebel sees community solar as a way to support Wisconsin farmers who could host the projects and continue farming. Community solar projects require less land, while still providing a stable income stream for landowner hosts.

“It really diversifies a source of income for our agricultural community where they can take maybe a field that's not quite as productive and it might be a perfect fit for a 30-acre solar field that would go on their property and provide them a source of income for a period of time,” Stroebel said.

Who gets to make power

As “natural monopolies,” utilities are the only provider in a designated service area. They also have a statutory responsibility to ensure the state has safe, reliable and affordable energy and are subject to regulation from the state’s Public Service Commission.

Madison Gas and Electric operates two community gardens including this one at Morey Field in Middleton.

America’s energy system was designed this way a century ago for efficiency. That model is being challenged as the energy transition unfolds and producing renewable energy is available to more entities. Distributed solar creates what some call the “prosumer” — the energy consumer who also produces power through rooftop solar arrays or community solar gardens.

“The whole advent of people being able to generate their own power is kind of a game changer,” said Tom Content, executive director of the Citizens Utility Board of Wisconsin.

While distributed generation means utilities have to build and invest in slightly fewer power facilities themselves, they still have to manage the flow of all the energy produced through the grid, whether or not they own it. Utility companies also earn a return on the investments they do make.

“They see customer-owned solar as a threat to their business model,” Content said.

Wisconsin utilities control the state's power grid and say that rooftop arrays and community solar gardens pass costs on to non-solar customers.

Many of Wisconsin’s large investor-owned utilities do offer limited access to community solar.

Madison Gas and Electric has two community gardens through its Shared Solar program and four more through a similar Renewable Energy Rider program. Customers of the Shared Solar program can offset up to 50% of their electricity use by paying a participation fee to the garden, plus 10.9 cents per kilowatt-hour for the power, according to Steve Schultz, spokesperson for MGE. Both of those gardens are currently full, serving around 2,000 customers.

Alliant Energy has one Wisconsin community solar garden operating in Fond du Lac and a Janesville project is in development.

Alliant and MGE oppose the Stroebel community solar legislation. Distributed generation like community and rooftop solar pass the cost of electricity transmission and grid maintenance on to other non-solar customers, utilities say.

“Our program is more self sufficient in that the subscribers are the ones sort of footing the bill there and reaping the benefits,” Alliant spokesperson Tony Palese said.

Access to solar power is in some ways limited. According to the federal Department of Energy, 42% of households and 44% of businesses cannot host a solar array of adequate size on their property. Less than 10% of the nation’s overall electricity generation capacity comes from solar panels, and community solar makes up less than 5% of that portion.

Maria McCoy is a Minneapolis-based researcher for the Energy Democracy Initiative at the Institute for Local Self Reliance, an organization that aims to take on “concentrated corporate power,” and supports community solar.

“Now more than ever electricity is really fundamental to life and should be a given, but it's not,” McCoy said. “Folks who are the least resourced and have least access to clean energy are also burdened with higher costs.”