FOND DU LAC – On a cold, wet winter morning, Olivia Halbur’s boots crunched across the melting snow and ice in her driveway as she made her way to the barn that houses her flock of sheep.

Halbur raises Texel sheep. They’re docile, stocky and known for their lean meat. The five dozen animals barely batted an eye as she climbed over the fence to hug and pet them.

“If you want a sheep to snuggle with, these are the guys to do it,” Halbur joked.

Though they were tucked in the barn to escape a January wind during a Cap Times reporter’s visit, in the summer the flock will follow Halbur up the hill behind her house and graze a 32-acre pasture. Her sheep will eat the grass under, around and between the rows of a 5-megawatt solar display, which will also provide the flock shade in the worst of the summer heat.

This idea of simultaneously using land for agriculture and solar energy generation is called agrivoltaics, and Halbur’s farm is one of the rare examples of it in Wisconsin. Although more developed in some parts of the Southwest and Northeast, the concept is relatively new here.

In response to the climate crisis and customer demand, utilities are closing coal plants and rapidly replacing them with massive solar-panel arrays. Farmers and rural Wisconsinites worry about thousands of acres being taken out of agriculture production at a time. Local researchers and environmental advocates are looking to agrivoltaics to determine if we can do both.

Halbur raises her flock on a fourth generation family farm with her husband. She sells sheep meat directly to consumers from her farm off of Highway 23 in Fond du Lac. A few years ago they were approached by a solar developer about hosting a small-scale array.

“It wasn't something we ever thought we'd do,” Halbur said. “But it looked (like) a wise diversification for the farm.”

Last December, the Halburs’ dairy cows were sold and after years of depending on fluctuating milk checks, solar seemed like a stable financial opportunity. They’re paid a rental price to host the solar and conduct the “vegetation management.” But Halbur said it was still a tough decision and knowing she could graze her sheep among the panels made all the difference.

“We would have never given up our land if we couldn't have still kept it as agriculture.”

There is currently no policy in Wisconsin to encourage agrivoltaics but there are signs that the concept could take off — potentially spurred by a new research facility the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Alliant Energy are building in Dane County. It’s also being looked at by environmental advocates as a solution to the land use concerns around solar development in rural communities.

Researchers and developers are experimenting with agrivoltaics, a type of farming that happens under and around solar arrays. The sheep on the Fond du Lac farm "Halbur's Heavenly Hill" will begin grazing a solar site this summer.

Increasing competition for land

Agrivoltaics most commonly takes the form of small animals grazing among the solar installation, like Halbur’s sheep. The livestock gets fed at the same time energy is produced. Some also consider planting native grasses and pollinator-friendly vegetation under panels to be agrivoltaics, since neighboring agriculture production benefits from a healthy pollinator ecosystem.

Growing crops under and between rows of panels is trickier, but farmers are finding success in Massachusetts and Colorado. In places like Arizona where water can be scarce and sunshine near constant, researchers have found that crops can benefit from the shade of the solar panels.

Sheep are the most commonly grazed livestock in agrivoltaic systems. Goats tend to chew on wires and jump on panels. Cows don’t have the same bad habits but do require the panels to be raised much higher, significantly increasing the cost of a solar array.

The most common crops used in agrivoltaics are vegetables or other hand-picked products. For machine-harvested crops to be grown in solar arrays, the rows of panels need to be spaced out so equipment can pass through, ultimately decreasing the amount of energy produced.

Agrivoltaic success stories are most common in small solar installations, those that take up 1 to 30 acres. But development of solar energy in Wisconsin is most often utility scale — hundreds to thousands of acres.

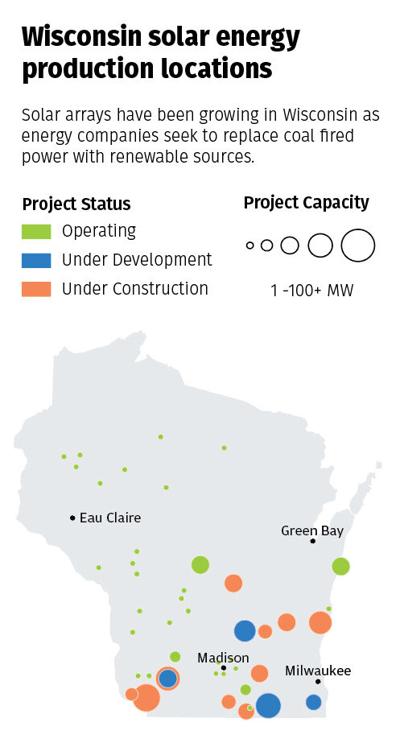

The Public Service Commission of Wisconsin has approved 4,176 megawatts of solar projects, encompassing over 29,000 acres.

The rapid deployment of utility scale solar has been met with concerns expressed at public meetings and through signs dotting yards and fields in rural communities. Residents across Wisconsin and the country have discussed and debated the effect solar power plants have on property values and the aesthetics and rural character of their communities. Farmers have expressed concerns for the potential of rising agricultural land rent prices and what taking farmland out of production means for the local agriculture economy and community.

SOURCE: Solar Energy Industries Association

“There are definitely folks that are interested in land use in the state,” said Stacy Schumacher, policy adviser at the Public Service Commission. “People (are) seeing something new, and certainly with the size of some of the projects, they're interested in what that means for their surrounding environment, their land use, and there's a lot of interest in that agricultural character of rural areas.”

Local governments throughout the state — and the nation — have imposed ordinances to stop or limit solar projects. According to an analysis by USA Today, at least 15% of counties in the country have halted utility scale solar or wind projects.

At the same time, Wisconsin’s dairy industry is consolidating and competition for land is increasing, making it harder for small and mid-size agriculture producers to remain in business. Wisconsin has lost nearly 30% of its dairy farms since 2017.

Diane Mayerfeld is a sustainable agriculture coordinator for UW Extension and said there’s been increasing land use conflicts and discussions about the trade offs when it comes to renewables. But most farmers aren’t anti-solar energy, she said, they’re just frustrated by the placement of some sites.

“Why is prime farmland the first place that we're generating, as opposed to flat roofs in urban areas,” Mayerfeld said they ask.

Leasing land to a solar developer can garner farmers hundreds of dollars more an acre than they’d get from cultivating crops on the same land. Solar contracts can be a reliable income source for farmers looking to retire. While taking land out of production for the duration of a 30-year lease is challenging, it's more attractive than selling the farm entirely and provides farmers an opportunity to pass the property on to the next generation.

Agrivoltaics is viewed as a potential path to meet the state’s renewable energy needs without sacrificing agriculture. In a 2021 survey, over 80% of respondents said they’d be more likely to support solar development in their community if it included agricultural production.

Will Fulwider is a regional crops educator with University of Wisconsin Extension and works with farmers in Dane and Dodge counties. He’s hoping researchers find ways that existing Wisconsin agriculture can fit in agrivoltaic systems. Sheep grazing is the most ready-made agrivoltaic option, but the state’s industry is small. However, if agrivoltaics proves a successful and profitable venture, farmers will adapt, Fulwider said.

Regarding the almost 30,000 acres of solar panels in the state, “There’s not enough sheep in all of Wisconsin to graze that,” he said.

Olivia Halbur will receive money for renting 32 acres of her land in Fond du Lac for a solar array as well as a payment for handling the "vegetation management" of the site when her sheep graze the grass growing under and around the solar panels.

UW looks for answers

This spring Alliant Energy and the University of Wisconsin-Madison will break ground on a 2.25 megawatt, roughly 15-acre solar array that will be used to study agrivoltaics at the university’s Kegonsa Research Campus 10 miles southeast of Madison.

Amanda Kesler, engineer at Alliant, called it a “sandbox” for the utility and UW researchers to test a variety of agrivoltaic systems. The design of the site reflects that — some of the array's panels will be elevated, some will be spaced out — “to make sure that it's as flexible as possible for any future research opportunities that present themselves,” Kesler said.

Researchers will study the soil and water quality of the solar site, its effect on wildlife, and the feasibility of grazing animals and growing crops among the array, said Josh Arnold, UW-Madison campus energy adviser.

The site is one of the university's living laboratories where the work of researchers and students informs the state’s policy and industry.

“In this transition with solar and clean energy and agriculture, we feel like we are going to be in a position to at least identify data and contribute to scientific knowledge that can then be used by policymakers or by the private sector, or by the general public,” Arnold said.

How to incorporate Wisconsin’s agriculture industry into the renewable energy transition is an underlying question for the researchers.

“All of the amazing history and culture around agriculture in our state … that's just a critical component of our state's identity,” Arnold said.

“How can we potentially be part of a conversation about, it doesn't have to be solar or agriculture. Maybe it could be both,” he said. “And maybe the university could play a role.”

Although the UW solar site is small, the knowledge gained could potentially be applied to the state’s existing large-scale solar projects in agriculture communities. Alliant has invested in the research station in hopes that the information discovered could determine what’s possible for larger projects, Kesler said.

Texal sheep graze a solar site in New York. Olivia Halbur, a farmer in Fond du Lac, raises the breed known for their lean meat.

Why farmland?

Land that works for agriculture also works for solar energy generation. It’s flat, clear, dry, spacious and often has access to the power grid. Additionally, economies of scale mean it’s cheaper for developers to build large continuous power plants than small distributed ones. Farmland is also sought out for solar because it's easier to coordinate than solar in urban space, said Mayerfeld, from the UW Extension.

It’s more cost effective “to build one large site on perfect land than to deal with a roof here and a parking lot there … and have 100 different contracts with 100 different landowners with different construction challenges,” she said, “versus working with 10 landowners and getting the same amount of space and having much less construction challenge.”

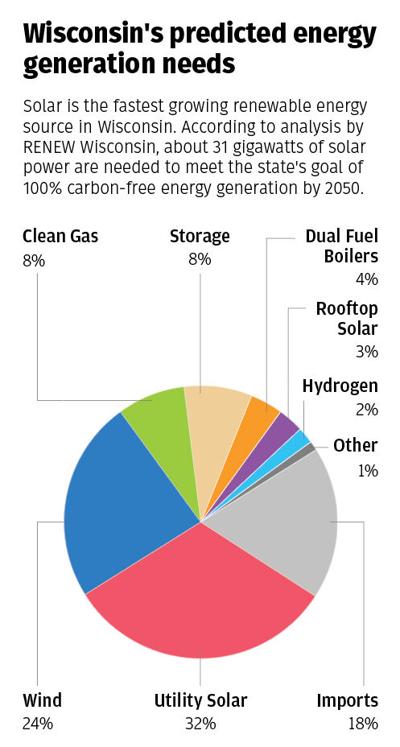

To achieve Wisconsin’s goal of using 100% carbon free energy by the year 2050, 28.3 gigawatts of utility scale solar will need to be installed in Wisconsin, according to RENEW Wisconsin, a renewable energy advocacy organization.

“That means that we would need about 198,000 acres of land to host utility scale solar in Wisconsin,” said Nolan Stumpf, development analyst at OneEnergy Renewables, who studied agrivoltaics during his master’s program at UW-Madison.

There are 14 million acres of actively cultivated farmland in the state. The amount needed for solar is about 1.4% of Wisconsin’s total, RENEW Wisconsin’s analysis states.

But, Stumpf acknowledged, “198,000 acres is still a lot of land and it's still a change to rural communities.”

Fulwider said he’s seen tensions flare in Dane and Dodge counties when utility scale solar is proposed. Farmers outside of Madison are already competing with housing developers for land and prices are going up, making it contentious when a landowner decides to take farmland out of agriculture production.

SOURCE: RENEW WISCONSIN

“I've heard from farmers that have gotten a lot of flak that have decided to put some of their land in solar panels,” Fulwider said. “They've faced a lot of criticism from surrounding neighbors.”

Other concerns about expanding solar in rural towns have to do with aesthetics and fears that country character will be lost. Folks don’t necessarily want to see a sea of glass where it was once waves of grain, corn or beans, Fulwider said. Neighbors and surrounding landowners feel like they get little say in whether a solar project comes to their town.

“People feel that they are always kind of getting the short end of the stick,” said Fulwider.

America’s energy grid is designed to take power from large generating facilities and distribute it widely. For the most part renewable energy can be generated anywhere. However, unless transmission infrastructure undergoes large upgrades, wind and solar farms will likely be sited where there is existing grid access.

Solar power plants and arrays will likely congregate in certain regions of the state, meaning those agriculture communities could lose a disproportionate amount of farmland.

“Not only does that reduce land access for people who are looking to farm but it could have knock-on effects for the economy … for all those businesses that serve those farmers,” Mayerfeld said.

Fulwider and Mayerfeld are optimistic that with some research, agrivoltaics can make sense for Wisconsin agriculture. Shade from raised panels could reduce heat stress in dairy cows or alfalfa could be cultivated between rows with smaller tractors. If farming among solar fields pencils out, Wisconsin producers will adapt, Mayerfeld predicts.

“If it turns out that sheep vegetation management under solar is profitable, farmers will acquire more sheep,” she said.

Fulwider said researchers and agriculture specialists need to be loud about the test cases that are successful “for utilities to see that this is an option.”

Halbur has been raising sheep since she was a child in 4-H. She's working to grow her flock to accommodate grazing the 32 acre solar site recently built on her farm.

OneEnergy develops a niche

A large red sign reading “Halbur’s Heavenly Hill” is visible from Highway 23 in Fond du Lac, attracting customers from near and far. Halbur sells her flock’s wool to a few spinners and crafters, but the main product is the meat. Customers can buy by the “half” or “whole” and Halbur recently got licensed to sell individual cuts of meat from the farm.

She’s also working to grow her flock to accommodate grazing the 32-acre solar array on her land less than a mile from an electrical substation.

Eric Udelhofen is vice president of development for the Midwest for OneEnergy Renewables, the developer of the array on Halbur’s farm. In a spacious downtown Madison office, he flipped through poster-board-size photos of solar projects they’ve built, identifying what was learned through each one.

“We are trying, as much as we can, to kind of push the boundaries on ways that we can incorporate farming and agriculture within the projects that we build,” Udelhofen said.

OneEnergy Renewables is a leader in the still small and brand new agrivoltaics industry. The developer has four small-scale solar arrays being grazed in the Midwest and will expand to three more this year.

They’re working toward growing vegetables under the panels at a site in Minnesota. Udelhofen said they’re also looking for ways to grow and harvest alfalfa — what dairy cows eat — among the solar sites, as well as how the land can continue to be used to spread manure.

“A lot of the projects that have run into a lot of opposition across Wisconsin have been in areas where there are large dairies that really need that land for forage but mostly for a manure application,” he said.

OneEnergy typically develops 1- to 10-megawatt projects and collaborates with researchers who need access to solar arrays to study agrivoltaics — including soil and water quality, effects on birds and wildlife, and the feasibility of various agriculture production. They hope what’s learned can be applied to larger scale solar power plants across the region.

Agriculture is different in every region of the country. Agrivoltaics will be, too.

Part of the reason OneEnergy Renewables is searching for workable solutions in agrivoltaics is because it “unlocks a lot of areas for development that would otherwise be out of reach,” Udelhofen said.

Agrivoltaics has the potential to preserve a community’s agricultural character — and economy — while solar energy develops. It can also ensure people have a stake and voice in the changes happening around them, Udelhofen said.

“If we don't figure out ways that we can be good agricultural neighbors, we're not going to succeed as an industry.”